Before it became a teatime staple or a snack time treat, chocolate arrived in Britain as something far more mysterious. Once rare, bitter, and steeped in ceremony, it gradually transformed into one of the nation’s most beloved indulgences.

From apothecaries to Aero bars, Britain’s relationship with chocolate is rich, layered, and far from finished. This is the story of how the nation made cocoa its own.

From Sacred Drink to Aristocratic Rarity

Cacao plants waiting to be harvested (Credit: RyanJLane via Getty Images)

Millennia before the cocoa bean ever reached British shores, it had already carved out a remarkable legacy in the lands of ancient Mesoamerica. The Olmec civilisation is believed to have been the first to cultivate the cacao plant, using its beans to produce a ritualistic drink. Far from the sugary treat we know today, this bitter concoction held sacred meaning – associated with power, ceremony, and status.

The Maya later refined the preparation, developing an early version of what we might now call hot chocolate. The Aztecs elevated its significance even further, treating cacao as a divine gift from the god Quetzalcoatl. So prized were the beans that they were even used as currency, as well as in ceremonial offerings.

It wasn’t until the 16th century that chocolate made its way to Europe, carried across the Atlantic by Spanish conquistadors. The exotic drink, initially consumed as a medicinal tonic, quickly found favour among the Spanish elite. From there, it spread across the continent, transforming from a sacred Mesoamerican ritual into a fashionable indulgence of Europe’s aristocracy.

Britain’s First Taste of Chocolate

Cocoa beans didn’t arrive in the UK until the 1650s (Credit: carlosgaw via Getty Images)

Britain was fashionably choco-late to the party. Cocoa beans didn’t arrive until the 1650s, and when they did, it wasn’t as a sweet indulgence but a bitter, medicinal drink. Sold by apothecaries, it promised to soothe everything from stomach aches to sorrow.

The aristocracy took notice. Soon, chocolate was being sipped alongside coffee and tea in the capital’s more refined coffee houses. Its popularity soared, leading to the rise of exclusive chocolate houses in cities like London, Bath, and Bristol. Some, including the famed White’s, would later evolve into prestigious gentlemen’s clubs.

These venues weren’t just social hubs. They were loud, lavish, and increasingly political – so much so that Charles II tried – and failed – to shut them down in 1675, declaring them “hotbeds of sedition.”

Chocolate, meanwhile, had found its place – expensive, exclusive, and deeply woven into the rituals of the British elite.

From Bean to Bar: The Chocolate Revolution Begins

Until the 18th century, chocolate was mostly drunk rather than eaten (Credit: Lilechka75 via Getty Images)

Until the 18th century, chocolate was primarily served as a drink, which the British typically mixed with water, milk, or both, as well as spices. It was also extremely laborious and time consuming to make, requiring the beans to be ground by hand.

As technology advanced, so did the possibilities for chocolate production. A key breakthrough was the invention of the cocoa press in 1828. The brainchild of Dutch chemist Coenraad van Houten, it removed cocoa butter from roasted beans and left behind a fine powder. This made chocolate more affordable, more versatile, and crucially, more suitable for solid forms.

It’s worth noting that, in 1729, almost a century before van Houten’s press, Bristol-based Walter Churchman received a patent for his water wheel press. Able to produce more chocolate powder and of a finer quality than ever before, Churchman’s Patent Chocolate business is considered Britain’s first specialist chocolate manufacturer. In 1761, the business, including the patent, was sold to Joseph Fry and John Vaughan, eventually becoming J. S. Fry & Sons.

Fry & Sons

Fry's created the world’s first solid chocolate bar (Credit: vovashevchuk via Getty Images)

Founded in Bristol in 1761 by Joseph Fry, J. S. Fry & Sons – commonly known as Fry’s – was a trailblazer in the British chocolate industry. In 1847, they created the world’s first solid chocolate bar, followed in 1853 by the first filled chocolate sweet, known as Cream Sticks. Their Fry’s Chocolate Cream, launched in 1866, became the first mass-produced chocolate bar. By the mid-19th century, Fry’s stood as one of the “big three” British confectionery giants, alongside Cadbury and Rowntree’s. At its peak, the company employed thousands, making it one of Britain’s largest manufacturing employers by the early 20th century. In 1919, it merged with Cadbury. While Fry’s Chocolate Cream bar still survives on modern shelves, the name was otherwise phased out.

Cadbury

An early advert for Cadbury's Cocoa (Credit: ilbusca via Getty Images)

In 1824, John Cadbury opened a grocer’s shop in Birmingham. Among the products sold were cocoa and drinking chocolate he prepared by hand. Cadbury attempted to expand his cocoa production, opening a factory in 1847. The business struggled. In 1861, his sons, Richard and George took over and changed its fortunes. They did so with the purchase of a van Houten cocoa press. This allowed them to produce a superior quality of chocolate to other manufacturers.

Expanding, they built the Bournville factory in 1879, building a town around it as a home for the workers. Then came the Dairy Milk bar. Introduced in 1905, it was made using a higher proportion of milk than competitors. The result? A creamier, sweeter product that became the country’s top selling bar by 1925.

Rowntree's

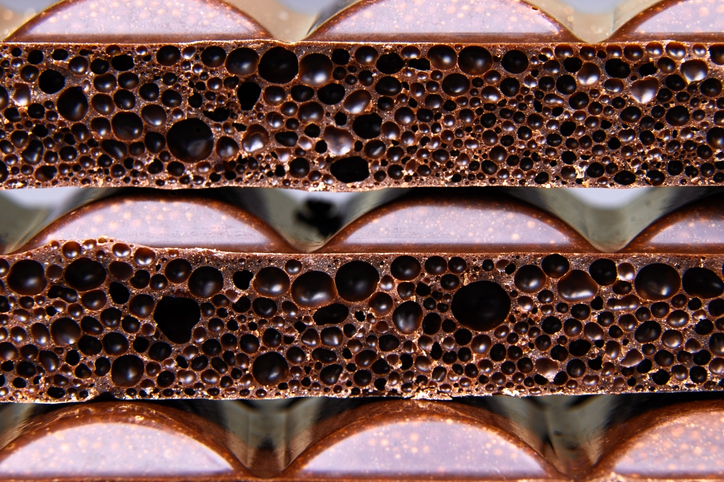

Rowntree's introduced the famous bubble chocolate bar in 1935 (Credit: Mikhail Kolomiets via Getty Images)

Further north, in York, Rowntree’s was founded in 1862. While their first forays were sweets, notably Fruit Pastilles, introduced in 1881, they went on to create many a classic British chocolate. In 1935 alone they introduced both the KitKat and the Aero bar. These were designed not only for mass appeal but also to be accessible and affordable – confections for the everyday consumer.

War, Rationing, and the Power of Comfort

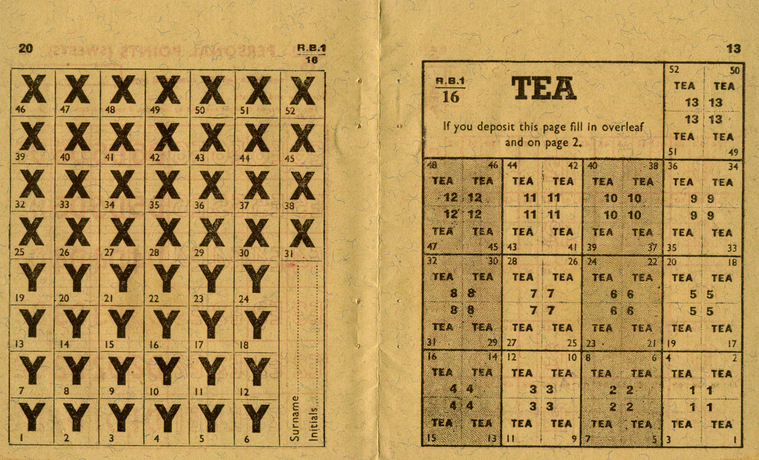

Most common items were rationed until the 1950s (Credit: MartinIsaac via Getty Images)

Chocolate’s role in British society shifted dramatically during the 20th century. During both World Wars it was included in soldiers’ rations, valued not just for energy but also as a morale booster. Cadbury even temporarily halted normal production during World War II to manufacture wartime supplies, including milk powder and chocolate for troops.

Back on the home front, rationing made chocolate a scarce treasure. Post-war children often recall the thrill of receiving a single bar, either as a treat or sent from relatives abroad. When rationing finally ended in 1954, chocolate reasserted itself as a beloved indulgence and everyday luxury.

The Global Age of British Chocolate

Our taste for chocolate has become more sophisticated (Credit: Stefan Tomic via Getty Images)

As the 20th century marched on, globalisation changed the landscape for chocolate manufacturers. Many British companies were absorbed by multinational giants – Cadbury by Mondelez (formerly Kraft Foods) and Rowntree’s by Nestlé. Such corporations dominate the market. However, British chocolate manufacturers have adapted, focusing on specialist and high end chocolate. Supermarkets have also joined the fray, with many producing their own brand bars.

Britain’s Favourite Bean

Happy World Chocolate Day! (Credit: Chris Ryan via Getty Images)

From sacred ritual to household favourite, the story of chocolate in Britain is one of transformation. First embraced as a luxurious drink for the elite, it evolved through innovation, industrial might, and changing tastes into the bars, buttons, and bites now found in every corner shop and kitchen cupboard.

Pioneers such as Fry’s, Cadbury, and Rowntree’s helped shape not only how chocolate was made, but what it came to mean – comfort in wartime, celebration in peace, and a small daily pleasure in ordinary life. Even as global giants now steer much of the market, Britain’s chocolate legacy continues, with specialist makers and nostalgic classics keeping the tradition alive.