On Monday, 15 February 1971, Britain woke up to a new kind of currency. Out went the old pounds, shillings, and pence – a system rooted in Roman times – and in came decimalisation, a streamlined monetary system built on units of ten. Nicknamed “D-Day,” Decimal Day marked one of the most significant overhauls in UK economic history.

But how exactly did this seismic shift play out, and what did it mean for everyday life? From shop tills to schoolrooms, we’re exploring the legacy of Decimal Day and the huge transition that reshaped a nation’s pocket change.

What was Decimal Day?

Great Britain's pre-decimal coinage (Credit: Nigel_Wallace via Getty Images)

On Monday 15 February 1971, the UK fundamentally changed its currency. On this date, the pound sterling officially changed from a complex system based on fractions to a decimal system based on multiples of ten, also known as base-10. This became known as Decimal Day.

Before the change, one pound was divided into 20 shillings, and each shilling into 12 pence, making calculations awkward and time-consuming. After Decimal Day, the pound kept the same value and name but was divided into 100 new pence. The shilling was abolished, and the value of the penny changed, with one new penny equal to 2.4 old pence. As a result, prices and payments became easier to calculate and understand, marking a clear and practical shift in everyday British currency.

Britain’s Old Money: A System Rooted in History

Sixpence coins from the reign of Edward VI (1547 - 1553) (Credit: Hein Nouwens via Getty Images)

To understand why Decimal Day mattered so much, it helps to appreciate just how deeply Britain’s traditional currency system was rooted in history. Its structure dated back to Roman Britain and later evolved into the ‘£ – s – d’ system, named after the Latin: libra, solidus, and denarius. For generations, people navigated it instinctively.

Yet by the mid-20th century, Britain was increasingly out of step. Many other countries had already adopted decimal systems, making calculations easier, trade smoother, and financial education simpler. South Africa, for example, decimalised its currency in 1961, a move closely watched by British policymakers.

As global trade expanded and computers began to appear in banks and businesses, Britain’s complex currency looked less like a tradition worth preserving and more like an obstacle to progress.

Why did Britain Decide to Decimalise?

The announcement to decimalise was made in 1966 (Credit: CHUNYIP WONG via Getty Images)

The idea of decimalisation was not new. Parliament debated it as early as the 19th century, and Britain even minted a decimal coin in 1848: the florin, worth one tenth of a pound.

What finally tipped the balance was practicality. By the 1960s, the UK was trading extensively with countries that already used decimal currency. Electronic accounting systems struggled with pounds, shillings, and pence. Teachers argued that children were spending years mastering a money system used almost nowhere else.

Following South Africa’s successful transition, the government set up a special committee in 1961 to examine Britain’s options. Its conclusion was clear. In March 1966, Chancellor of the Exchequer James Callaghan announced that Britain would adopt a decimal system with 100 units to the pound, allowing around five years for preparation.

Preparing the Nation for Decimal Day

The Royal Mint moved from Tower Hill where it had been since 1812 (Credit: RockingStock via Getty Images)

What followed was one of the most carefully managed transitions in peacetime Britain.

New Coins, Introduced Gradually

Decimal coins did not suddenly appear in 1971. The 5p and 10p coins entered circulation in 1968, deliberately matching the size and value of the shilling and florin. A new 50p coin followed in 1969, replacing the ten-shilling note.

By staggering these releases, three major decimal coins were already familiar by the time Decimal Day arrived. Behind the scenes, almost six billion new coins were required for decimalisation, and the sheer scale of production helped drive the Royal Mint’s move from Tower Hill to its new Llantrisant facility, which opened in 1968.

Banks, Businesses & Machines

The Decimal Currency Board worked closely with banks, retailers, and manufacturers to convert tills, accounting systems, price labels, and computers. By mid-1970, most technical changes were complete or scheduled.

Banks closed from the afternoon of 10 February until the morning of 15 February to convert accounts and records. Stock exchanges, post offices, and transport services adjusted operations so the switch could happen with minimal disruption.

Teaching the Public

Perhaps most crucially, the public was prepared. From 1969 onwards, Britain saw a vast information campaign using leaflets, posters, TV programmes, radio broadcasts, and even pop songs.

The BBC aired short educational segments called Decimal Five, while ITV’s Granny Gets the Point used drama to explain the new system. Around 20 million explanatory booklets were delivered to households, ensuring most people had a simple guide close to hand.

Shops displayed dual pricing, schools taught both systems side by side, and staff were trained to give change confidently in new pence.

Resistance and the Sixpence Debate

One of the last sixpence pieces minted in 1967 (Credit: Scott O'Neill via Getty Images)

Not everyone welcomed the change. Few coins inspired more affection than the sixpence – the “tanner” – and its planned disappearance sparked public outcry. Although logically it had no neat place in a decimal system, opinion ran so strong that the government allowed the sixpence to remain legal tender for several years after Decimal Day. The last sixpences for general circulation were minted in 1967, and after decimalisation it continued as a 2.5p coin until it was demonetised in 1980.

Decimal Day: A Symbolic Moment

Post-decimalisation British coins (Credit: efesan via Getty Images)

By the morning of 15 February 1971, Britain effectively woke up decimal. Shops opened with prices shown primarily in new money. Old coins were accepted, but change came back decimal. British Rail and London Transport had already switched fares a day early. While there was caution, and the occasional complaint about the tiny new halfpenny, the day itself was widely described as smooth, orderly, and almost anticlimactic. That calm was no accident. Decimal Day worked precisely because so much had already changed.

Life After Decimal Day

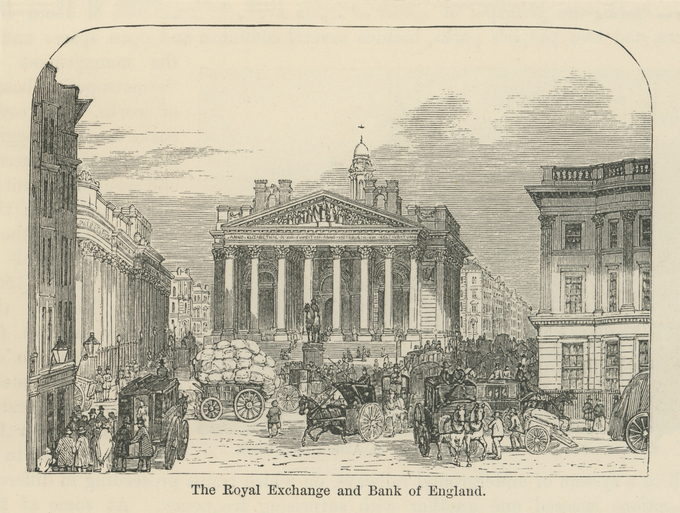

The world-famous facade of the Bank of England (Credit: mikroman6 via Getty Images)

The adjustment did not end in 1971. Many people continued to think in old money for years, particularly when dealing with large sums. Over time, though, decimal currency became second nature.

Coins continued to evolve. The 20p arrived in 1982, followed by the £1 coin in 1983. The halfpenny disappeared in 1984. The 5p and 10p were resized in the early 1990s, finally ending the use of shillings and florins.

By 1992, every coin in circulation bore the head of the reigning monarch, something not seen since medieval times. Decimal Day, once feared as a disruptive leap into the unknown, had quietly reshaped British life for good.

Today, few people give much thought to the simplicity of 100 pence to the pound. Yet that simplicity was hard-won, the result of careful planning, public education, and a willingness to let go of centuries of tradition.