Literacy – the ability to read and write – has a long and complex history, evolving from a skill held by a privileged few into a foundation for modern societies. Indeed, for much of human existence, the ability to read and write was exclusive and regarded as a gateway to knowledge, power and influence.

Yet over the centuries, changes in how people communicated, shared stories, and recorded information gradually shaped the meaning and role of literacy into how we understand it today. The concept shifted beyond basic word recognition to include the broader social and cultural impact of being able to read and write, ensuring that progress wasn’t just for the few, but for the many.

The move toward mass literacy is one of humanity’s most significant achievements, driven by changing societies and the spread of education. Today, reading and writing are seen not only as vital skills but also as a way to acquire greater knowledge, values, attitudes and behaviours that can, in the words of UNESCO –

‘foster a culture of lasting peace based on respect for equality and non-discrimination, the rule of law, solidarity, justice, diversity, and tolerance and to build harmonious relations with oneself, other people and the planet.’

In this article, we’ll write the story of literacy’s evolution as well as explaining how International Literacy Day is a remarkable global challenge.

What is International Literacy Day?

The wonder of the written word (Credit: Marco VDM via Getty Images)

According to UNESCO, at least 739 million youth and adults around the world lack basic literacy skills. At the same time, 40% of children aren’t reaching minimum proficiency in reading, and in 2023, 272 million children and adolescents didn’t go to school.

Since 1967, International Literacy Day – ILD – has been marked around the world, not just to remind us all how much fun it it to get lost in a good book, but also to remind policy-makers, practitioners, and the public of the critical importance of literacy for creating a more peaceful, and sustainable society.

ILD 2025

Each year, International Literacy Day has a theme. In past years, themes have included Literacy and Health, Literacy and Empowerment, Literacy and Peace, and Promoting Literacy for a World in Transition. For 2025, the theme is Promoting Literacy in the Digital Era.

The idea is that it highlights the need for everyone to gain the skills to read, write, and fully participate in our increasingly digital world. The aim is to help people everywhere access, understand, and use digital information – ensuring no one is left out as technology transforms how we learn, work, and connect. The initiative also calls attention to digital divides and strives for greater inclusion, empowering people with the critical skills needed for personal growth and community advancement in an age of rapid technological change.

But how did we get from stones to screens? Are you ready to turn the page on the fascinating history of literacy? Write on!

The Origins of Literacy

Heiroglyphics from the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Egypt (Credit: Francesco Riccardo Iacomino via Getty Images)

The story of literacy begins long before the alphabet we recognise today. Around 10,000 years ago, the earliest known proto-writing emerged in Mesopotamia, where small clay tokens were used to count and track goods such as grain, oil, and livestock. These simple symbols (a triangular shaped token might have represented grain, a circular-shaped token might have represented oil, etc.) laid the groundwork for writing, helping merchants and administrators keep records of agricultural products and trade. While this wasn’t writing as such, this early system of communication was practical and became rooted in everyday economic life.

Over time, these tokens began to be stored inside clay envelopes (bullae), which were sometimes sealed and marked on the outside with impressions of the tokens inside. Eventually, instead of placing tokens in a bulla, people began pressing the tokens directly into clay tablets. This shift – around 3500 BC – marks the transition toward proto-writing.

By about 3200 BC, true writing systems developed independently in several ancient civilisations. In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians created cuneiform – a wedge-shaped script impressed with a reed stylus onto clay tablets. Initially used for accounting and administration, cuneiform eventually recorded stories, laws, and even poetry, marking the beginning of literature. Around the same time, Egyptian hieroglyphics appeared, used for sacred and monumental texts and royal inscriptions, and sometimes written on papyrus.

In the Far East, Chinese characters developed during the Shang dynasty around 1400 BC, beginning as symbols for divination on oracle bones. These complex characters evolved over centuries into the rich and intricate writing system still in use today.

Across these cultures, literacy was closely tied to power, social status and governance, with priests and administrators controlling much of the written word. Writing remained an elite skill for centuries, mastered only by highly-trained scribes and scholars who learned writing, mathematics, and various practical subjects essential for managing temples, palaces, and trade.

In China for example, the imperial examination system required deep knowledge of classical texts, and only those who passed could join the bureaucracy, making literacy a key path to official power.

The Alphabet

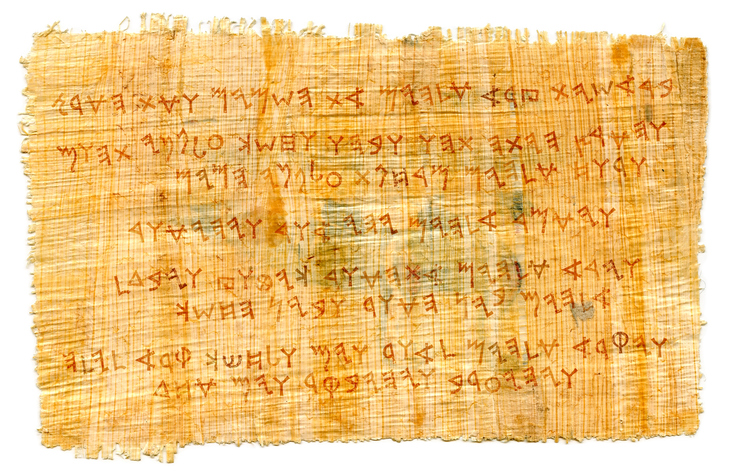

The consonantal proto-writing of the ancient Phoenicians (Credit: Adobest via Getty Images)

While it still remains subject of some debate, the first alphabet is believed to have developed sometime between 2000 BC and 1500 BC in the Sinai Peninsula (according to some, by workers in Egypt’s turquoise mines) who adapted Egyptian hieroglyphs into a simplified set of symbols representing sounds rather than ideas or objects. This early system, known as the Proto-Sinaitic script, was an important step toward phonetic writing, capturing the sounds of language rather than complex pictorial signs.

For example, the hieroglyph for ‘house’ became the letter for the ‘b’ sound because the Semitic word for house, bayt, begins with ‘b’. This simplified the writing system from hundreds of complex symbols to 30 – 40 characters, making literacy more accessible.

The Phoenician Traders

Around 1100 BC, the Phoenician alphabet emerged and became the first widely used phonemic script containing about two dozen letters representing consonant sounds. The Phoenicians were maritime traders, and their alphabet spread throughout the Mediterranean, influencing many other writing systems due to its simplicity and adaptability. This script was known as an abjad, an alphabet where only the consonant sounds were represented and the vowels were inferred by the reader.

The Greek Adaptations

The Greeks later adapted the Phoenician alphabet around 800 BC, adding vowels and creating what is considered the first ‘true alphabet’ representing both consonants and vowels. This Greek alphabet then influenced the Latin alphabet used by the Romans, which became the foundation for many modern alphabets, including English. Other scripts like Aramaic, Hebrew, and Arabic also descended from the Phoenician system, spreading alphabetic writing across West Asia, North Africa, and parts of Europe.

The Development of Literacy Through the Middle Ages

Medieval scribes would copy manuscripts by hand (Credit: mikroman6 via Getty Images)

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century AD, literacy in Western Europe became mostly confined to the Christian Church. In the Early Middle Ages, monks and clergy copied manuscripts by hand onto parchment, making books very expensive and rare. During this time, literacy was concentrated among religious leaders and, later, the political elite.

If we fast-forward to around the eleventh to thirteenth centuries (known as the Central Middle Ages), literacy began to spread beyond the clergy to include merchants, administrators, and royalty. This expansion was helped by the reintroduction of classical texts through Islamic scholars and the gradual spread of paper manufacturing in Europe, which started in Spain. Written use of vernacular (informal, spoken) languages also increased, making written communication much more accessible.

Although formal education was still centuries away for the masses, some literacy skills reached broader groups. Historical records show that even those considered illiterate at the time engaged with texts by commissioning or using legal and administrative documents. This indicates a growing participation in literacy beyond the educated elite.

The Print Revolution and the Path to Mass Literacy

Johannes Gutenberg with a document printed on his revolutionary press (Credit: FPG via Getty Images)

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the movable-type printing press in the 1450s revolutionised book production by drastically reducing the time and cost required to produce books. This breakthrough – the start of the information revolution – transformed books from rare, expensive items that only the rich and powerful could access, into books, leaflets and posters which became widely available and accessible to all. This innovation helped to fuel the Renaissance, accelerated the spread of literacy and education, and provided a much broader range of people with opportunities to learn and access information, which had previously been out of reach.

The Protestant Reformation

In the sixteenth century, reformers like Martin Luther recognised the power of the printed word and promoted individual access to the Bible by translating it into vernacular languages. This encouraged widespread reading and directly linked literacy to religious and social change, empowering ordinary people to engage with their faith independently.

The Enlightenment & The Industrial Revolution

Enlightenment ideals championed universal education, leading several European countries – Prussia & Bavaria (two major German states at the time, now part of modern Germany), Sweden, Denmark, Poland and France – to introduce literacy programmes and to pioneer national education frameworks in the eighteenth century. Though widespread literacy initially remained mostly among the middle and upper classes, the Industrial Revolution accelerated the demand for educated workers who could read technical instructions, fuelling further growth in literacy.

Great Britain started developing literacy efforts during this period but introduced compulsory state schooling later in the nineteenth century.

Literacy in the Twentieth Century & Beyond

The digital age is here! (Credit: Wavebreakmedia via Getty Images)

During the twentieth century, literacy grew rapidly as countries around the world set up public education systems that made schooling available to nearly all children. Programmes focused on teaching basic reading and writing skills became a priority, helping people from all sorts of backgrounds learn to read and write. Libraries and new books also made it easier for people to practice and use their literacy skills in everyday life.

With the digital age, literacy has evolved beyond just reading and writing on paper. Now, people need to understand how to use computers, smartphones, and the internet to find, evaluate, and share information. This new kind of literacy, called digital literacy, is essential for many parts of modern life – from learning and working to staying connected with others.

Today, being literate means having skills to navigate both traditional texts and digital platforms. While technology offers amazing opportunities for learning and communication, it also has its own challenges, chief among which is the unequal access to devices and education, something that International Literacy Day 2025 is attempting to remedy.