Archaeology often conjures images of sunbaked trenches and stone relics slowly emerging from the dust. But some of the most astonishing discoveries come from places where boots sink rather than crunch. Wetlands, with their dark waters and oxygen-poor soils, have a remarkable way of pausing time, preserving materials that would otherwise vanish, from finely worked wood and supple leather to food remains frozen in their final moments.

What makes wetland archaeology especially compelling is its intimacy. Instead of grand structures or long-term settlement patterns, these sites reveal singular acts: a sword deliberately placed in a bog, a shoe lost on a timber trackway, an offering lowered into still water. So, what happens when nature plays the role of archivist? Let’s explore some of the most extraordinary discoveries ever drawn from the world’s wetlands.

The Tollund Man, Denmark

Tollund Man was found almost perfectly preserved in a Danish peat bog (Credit: carstenbrandt via Getty Images)

Perhaps the most famous bog body in the world, the Tollund Man was discovered in 1950 in the Bjældskovdal Mose, a peat bog near Silkeborg in north-central Denmark. Scientific dating places him between 405 and 380 BCE, firmly within the Iron Age. His preservation was so lifelike that the men who found him initially believed they had uncovered a recent murder victim.

His leathery skin, serene facial features, and short-cropped stubble survived thanks to the bog’s oxygen-poor, acidic chemistry. He was found unclothed except for a leather cap and belt, with a leather rope still around his neck, indicating he was hanged. Now displayed at Museum Silkeborg, the Tollund Man offers one of the clearest windows into Iron Age life and death.

The Sweet Track, England

The ancient timber track was found beneath the Somerset Levels in 1970 (Credit: David Clapp via Getty Images)

Hidden beneath the Somerset Levels lies one of the world’s oldest known timber trackways. The Sweet Track, discovered in 1970, crossed around a mile of reed swamp, linking the island of Westhay with the drier Polden ridge to the south. Tree-ring dating shows it was built some time around 3800 BCE, at a moment when farming and settled life were only just taking hold in Neolithic Britain.

Carefully engineered, the track was formed by angled wooden poles driven into peat to hold planks in place, secured with long pegs. Nearby pottery contained traces of cow’s milk fat, the earliest evidence of dairy farming in the UK. Its survival reshaped views of Neolithic skill, organisation, and wetland use.

The Windover Bog Bodies, United States

It's amazing what can be found in Florida's peat bogs... (Credit: Peter Essick via Getty Images)

In Florida, peat mining in the 1980s led to the discovery of a prehistoric burial site now known as Windover. Used between roughly 10,000 and 5,000 years ago, the site contained more than 160 burials from the Archaic period.

Thanks to the waterlogged conditions, not only were skeletons preserved, but tissue samples survived in certain places. This allowed scientists to extract ancient DNA, offering rare insight into early populations, their health, diet, and genetic ancestry.

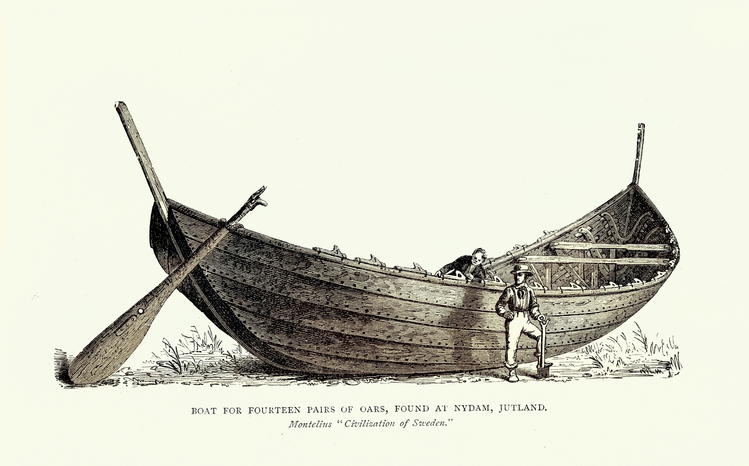

The Nydam Boat, Denmark

The Nydam Boat, found in 1863 (Credit: duncan1890 via Getty Images)

Pulled from the Nydam Bog in southern Denmark during excavations led by Conrad Engelhardt in 1863, the Nydam Boat ranks among the most significant wetland finds in maritime archaeology. Alongside large deposits of weapons and military equipment, excavators uncovered the remains of three boats. One, a remarkably preserved oak vessel, dating to around 320 CE.

Over 75 feet long and powered entirely by oars, the boat lacked a mast or sail, marking it as a formidable rowing craft rather than a sailing ship. Its construction forms a clear technological bridge between earlier boats such as Hjortspring and later Viking vessels. Preserved by the bog’s waterlogged conditions, the Nydam Boat reveals how wetlands safeguarded not just objects, but pivotal moments in seafaring development.

The Must Farm Settlement, England

Stonehenge is the most famous Bronze Age monument in the UK (Credit: jessicaphoto via Getty Images)

Often dubbed “Britain’s Pompeii,” the Must Farm site in Cambridgeshire was uncovered during quarry work and excavated between 2015 and 2016. The stilt-built village appears to have been occupied for less than a year before a catastrophic fire in around 850 BCE caused the structures to collapse into the river below, sealing their contents in waterlogged silt.

The wetland environment preserved wooden buildings, textiles, tools, and food remains in extraordinary detail. Everyday objects such as bowls, woven fabrics, and even footprints offer a snapshot of daily life at the end of the Bronze Age, rarely seen elsewhere.

The Shigir Idol, Russia

The Shigir Idol was found in Russia's Ural Mountains in 1894 (Credit: Aleksandr Zubkov via Getty Images)

Discovered at the bottom of a peat bog in the Ural Mountains in 1894, the Shigir Idol is the oldest known monumental wooden sculpture in the world. Carved from a single larch tree around 12,000 years ago, it predates both Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids by millennia.

Originally standing almost 17 feet tall, the idol is etched with geometric motifs, zigzags, and stylised human faces arranged along its length. Recent analysis confirms it was made by hunter-gatherers at the end of the last Ice Age. Its remarkable survival is entirely due to the bog’s preservative conditions, while the complexity of its markings demonstrates that symbolic expression and large-scale woodcraft existed far earlier than once assumed.

The Grauballe Man, Denmark

Danish peat bogs kept the breakfast of a 2,000 year old man complete (Credit: Westersoe via Getty Images)

The Grauballe Man was discovered on 26 April 1952 in the Nebelgaard Mose peat bog, just west of Aarhus. Thanks to the bog’s acidic conditions, his skin, hair, and even fingerprints were preserved for more than 2,000 years. Yet the Grauballe Man was not finished with his revelations. Scientific analysis of his stomach contents revealed his final meal: a porridge made from grains and weeds. This discovery offered insight into Iron Age diet and lifestyle.

Prehistoric Canoes, Netherlands

Replicas of prehistoric canoes (Credit: Lingbeek via Getty Images)

The wetlands of the Netherlands have yielded numerous prehistoric dugout canoes. Carved from single tree trunks, these boats were essential for travel, fishing, and trade in a low-lying, water-rich landscape.

Their preservation provides rare evidence of early watercraft technology and the central role wetlands played in shaping human movement and settlement. Without waterlogged conditions, such wooden vessels would have vanished without trace.

The most famous of these finds is the Pesse canoe. Dating back to the early Mesolithic, roughly between 8200 and 7600 BCE, it’s said to be the oldest boat in the world.

The La Draga Neolithic Village, Spain

Lake Banyoles, northeastern Spain (Credit: Toni M via Getty Images)

On the shores of Lake Banyoles in northeastern Spain lies La Draga, a Neolithic lakeside village discovered in the 1990s. Dating to around 5300 BCE, it’s one of the earliest farming settlements in the western Mediterranean.

Waterlogged soils preserved wooden tools, sickles, baskets, and building materials, shedding light on the transition from hunting-gathering to agriculture. The site reveals how early farmers adapted to wetland environments, using lakes and marshes as sources of food, transport, and protection.

Kuk Swamp, Papua New Guinea

The Papua New Guinea Highlands (Credit: Timothy Allen via Getty Images)

High in the New Guinea Highlands, around 4,900 feet above sea level, Kuk Swamp has transformed the understanding of early agriculture. Spanning some 280 acres of wetlands, the site preserves evidence of remarkably persistent land use stretching back possibly 10,000 years.

Archaeology reveals a clear technological shift from plant exploitation to true agriculture around 7,000 to 6,400 years ago, based on the cultivation of bananas, taro, and yam through vegetative propagation. Waterlogged soils protected cultivation mounds, planting pits, and later drainage ditches dug with wooden tools, charting the gradual reclamation of the swamp. Kuk is one of the world’s strongest examples of independent agricultural development, showing how farming practices evolved over millennia in a challenging wetland landscape.

From Marsh to Museum

The world's wetlands are fascinating archaeological time capsules (Credit: Steve Handy / 500px via Getty Images)

From ritual sacrifices and ancient roads to villages, boats, and works of art, wetlands have proven to be unparalleled archaeological time capsules. While dry land often strips history down to stone and bone, waterlogged environments preserve the textures of life itself: wood, cloth, food, and even bodies. These amazing environments have become the ultimate time capsules, allowing us to glimpse the distant past like never before.