Food tells the story of a nation better than almost anything else. In Britain, every era has left its own stamp on the plate – from the wild berries and smoked meats of prehistoric life to the elaborate sugar sculptures of Tudor banquets and the comforting fish and chips of the industrial age.

This journey through Britain’s kitchens isn’t just about what people ate, but why. It reveals how survival, status, and global influence turned a patchwork of simple staples into a cuisine that’s endlessly evolving – and far richer than its old reputation suggests.

Neolithic

People have been foraging for thousands of years (Credit: vincent janssen / 500px via Getty Images)

Until the 4th millennium BC, life was very much about hunting, fishing, and foraging. People roamed in small, mobile groups, following seasonal food sources such as red deer, boar, fish, shellfish, berries, nuts, and roots. Simple tools, often made of flint, supported this way of life, while woodland clearings were created through controlled burning to attract game and encourage the growth of useful plants.

Around 4000 BC, however, a decisive shift took place. The arrival of domesticated animals and crops marked the beginning of Britain’s Neolithic period, when people began settling more permanently. Over the following centuries, meat and milk from pigs, cattle, sheep, and goats became dietary staples. Fresh milk itself was rarely drunk, as lactose intolerance was widespread; instead, it was processed into butter, yoghurt, and cheese. Grains were grown, though usually on a smaller scale, and complemented the produce of livestock rather than replacing it.

This transition did not erase older traditions entirely. Wild foods – berries, nuts, mushrooms, and plants such as nettle and crab apple – still found their place in the diet. Hunting, though less central, remained part of life, now managed more deliberately alongside farming. In this way, Britain’s Neolithic communities carried the memory of their Mesolithic ancestors even as they embraced agriculture and settlement.

Bronze Age

Bronze Age communities grew and harvested fields of spelt wheat (Credit: Andyworks via Getty Images)

The Bronze Age built on the Neolithic shift to farming, carrying it a step further. Communities established some of the first permanent fields, and the range of crops widened to include beans, peas, and spelt wheat. These provided valuable variety and nutrition, while new preservation methods ensured harvests could last through the colder months. Cooking also changed as metal pots and pans replaced stone and wooden tools, allowing meals to be prepared with greater care and subtlety. Life was still largely about sustenance, yet these advances marked a clear progression. The truly dramatic changes, however, would arrive with the Romans, who brought new flavours, farming practices, and a taste for sophistication.

Romans

Romans in Britain enjoyed lavish feasts (Credit: imageBROKER/Sunny Celeste via Getty Images)

When the Romans invaded in AD 43, they did not come empty-handed. Roads and aqueducts carried more than soldiers; they brought olives, grapes, figs, and improved farming techniques. Roman Britain saw the introduction of orchards, structured crop rotation, and herbs including coriander and dill.

Dining was elevated from survival to sophistication. Roman villas boasted heated kitchens, and urban centres offered bustling markets. They also introduced sauces akin to garum, a pungent fish-based condiment not unlike today’s anchovy paste. In fact, the Roman taste for complexity arguably sowed the seeds of Britain’s later obsession with condiments.

Saxons and Vikings: Hearth and Home

The Saxons and Vikings returned to more simpler fare (Credit: Sonya Kate Wilson via Getty Images)

With the collapse of Roman rule came a return to simpler fare. Anglo-Saxons leaned heavily on porridge, bread, cheese, and preserved meats. Their diet was hearty, designed to keep communities warm through unforgiving winters.

The Vikings added to the mix, not just raiding but also trading. They brought smoked fish, improved salting methods, and a penchant for mead. Feasts centred around roasted meats and ale, giving us an early glimpse of the communal banquets that still define many British celebrations.

Norman Conquests and Courtly Kitchens

Meat pies were a Norman staple (Credit: Sonya Kate Wilson via Getty Images)

After 1066, the Normans introduced a distinctly continental flair. Spices such as cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg began arriving through new trade routes, though only the wealthy could afford them. Noble tables often featured elaborate roasts, intricate pastries, and the first stirrings of what might be called haute cuisine.

Meanwhile, peasants subsisted largely on pottage, a thick vegetable stew bulked out with grains. The stark contrast between rich and poor diets highlighted social divides, a theme that would persist across centuries. Still, Norman influence expanded Britain’s palate and while also firmly establishing meat pies as a staple, a tradition that continues from steak-and-kidney to Cornish pasties.

The Tudor Table: Spice and Spectacle

Exotic spices and dried fruit transformed British cookery (Credit: Inga Rasmussen via Getty Images)

By the Tudor era, exploration and trade had ushered in a new world of flavours. Sugar, once rare, became a symbol of status. Banquets glittered with elaborate sugar sculptures known as subtleties, while spices and dried fruits transformed puddings from humble to indulgent.

Henry VIII’s court was infamous for its gluttony – roasted swan, whole peacocks, and venison pasties featured in extravagant displays. Yet outside royal halls, the diet remained plain: bread, ale, cheese, and seasonal vegetables. The widening gap between elite feasts and everyday fare was, quite literally, hard to swallow.

Georgian Refinement and Industrial Fuel

Afternoon tea became - and remains - a British institution (Credit: fancy.yan via Getty Images)

The 18th century saw refinement in both kitchen and table manners. Georgian dining was influenced by French chefs and an emerging middle class keen to show sophistication. Afternoon tea – introduced by Anna, Duchess of Bedford – became a fashionable ritual, eventually cementing itself as a national institution.

Simultaneously, the Industrial Revolution altered eating habits for working families. Urbanisation meant less access to fresh produce, so salted, pickled, and canned goods became crucial. Street foods such as pies, oysters, and fried fish fed factory workers quickly and cheaply, laying foundations for Britain’s most enduring takeaway: fish and chips.

Victorian Variety and Empire on a Plate

Exotic tea from China flooded into Britain in the 19th century (Credit: zhihao via Getty Images)

The Victorian era truly globalised British cuisine. Empire expanded trade networks, and with them came curry powders from India, tea from China, and chocolate from the Americas. Curry houses began appearing in port cities, while tea drinking transformed from luxury to daily necessity.

Cookbooks flourished, with Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management setting new standards for domestic kitchens. Yet Victorian Britain also battled poverty and malnutrition, with many families surviving on bread, dripping, and weak tea. Food, once again, reflected class distinction – lavish multi-course meals for some, bare sustenance for others.

The Wars: Rationing and Reinvention

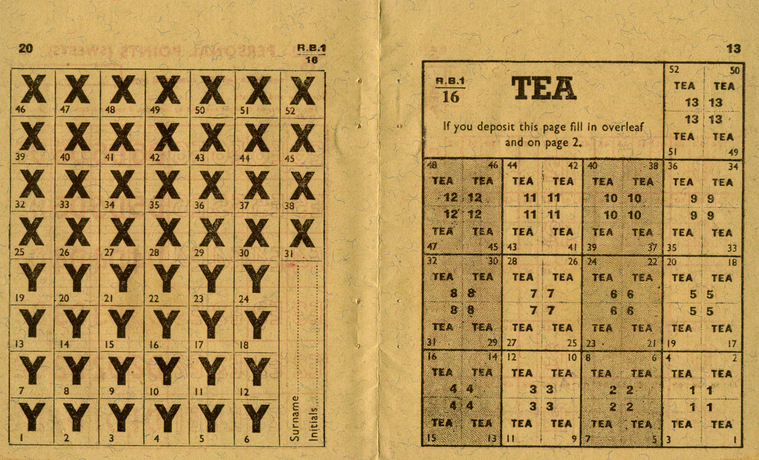

Most common items were rationed until the 1950s (Credit: MartinIsaac via Getty Images)

Both World Wars forced Britain to rethink its relationship with food. Imports dwindled, rationing was introduced, and “make do and mend” applied as much to kitchens as wardrobes. Creative substitutions emerged: carrot cakes, powdered eggs, and Spam.

Despite austerity, rationing arguably improved health for many, reducing reliance on sugar and fat while ensuring fairer distribution. The government encouraged home-growing through the “Dig for Victory” campaign, turning gardens and allotments into lifelines.

Post-War Britain: From Bland to Bold

Chicken tikka masala has become Britain's favourite dish! (Credit: Teo Maniu / 500px via Getty Images)

The post-war years initially lingered in culinary drabness, with rationing lasting until 1954. However, immigration soon began reshaping British tastes. Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani, and later Middle Eastern and East Asian communities enriched the national menu.

Chicken tikka masala famously became a symbol of Britain’s love affair with curry, while Chinese takeaways spread across towns and cities. Italian restaurants introduced pizza and pasta, challenging the meat-and-two-veg tradition. Slowly but surely, Britain’s plate diversified.

The Modern Feast: Global Meets Local

Shepherd's Pie - lovely bubbly! (Credit: istetiana via Getty Images)

Today, British food is as eclectic as its people. Traditional dishes – roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, shepherd’s pie – remain cherished, often revived in modern gastropubs. Yet they now sit alongside sushi counters, Lebanese street food, and sourdough bakeries.

There’s also a renewed appreciation for local, seasonal produce. Farmers’ markets thrive, championing British cheeses, heritage vegetables, and artisanal breads. Sustainability and food miles have become pressing concerns, reshaping how people shop and cook.

And of course, tea still reigns supreme, whether brewed strong with milk or dressed up in artisanal blends. The national beverage has never really left the table.

A Nation’s Palate in Constant Motion

What better way to finish than with apple crumble and custard! (Credit: SGAPhoto via Getty Images)

From porridge to posh puddings, pottage to pasta, Britain’s culinary story is one of adaptation. The so-called “bland” reputation doesn’t quite hold water, or gravy. Instead, British food reflects resilience, curiosity, and a readiness to absorb the best of the world while holding onto comforting classics.