Few writers have peered into the future with as much confidence or imagination as Jules Verne. Writing in the mid-to-late 19th century, Verne filled his adventure novels with machines, vehicles, and technologies that seemed wildly implausible to his contemporaries. Submarines that could roam the oceans for months. Projectiles fired into space. Instant global communication. At the time, these ideas belonged firmly in the realm of fantasy. And yet, more than a century later, many of them feel uncannily familiar. Others, however, missed the mark by a nautical mile.

So how well did Verne really do at predicting the future? This scorecard puts his most famous technological visions under the microscope, ranking them from spectacular misfires to astonishingly accurate foresight. Strap in, this is retro-futurism with receipts.

Category: “Nope” | When Imagination Outran Reality

Jules Verne's Nautilus (Credit: homeworks255 via Getty Images)

The Columbiad Space Cannon

From: From the Earth to the Moon (1865)

Verne’s vision of space travel involved an enormous cannon – the Columbiad – designed to fire a crewed projectile from Florida to the Moon. While the location was eerily prescient (modern NASA launches do indeed depart from Florida), the method was… less so.

The physics are unforgiving. The acceleration required to launch humans via cannon would instantly pulverise its occupants. Even Verne acknowledged some practical challenges, but he underestimated just how lethal such forces would be.

Verdict: A bold idea that collapses under basic Newtonian mechanics.

Score: 1/10 | Enthusiastic, but fatally flawed.

Undersea Living

From: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870)

Captain Nemo dreams not just of exploring underwater in the Nautilus, but of humanity eventually living permanently in the ocean depths. While there have been experimental underwater habitats and research stations, permanent undersea living remains impractical. The challenges are immense, whether supply limitations in long-range vessels, or the pressure, corrosion, energy supply, and psychological strain of potential undersea habitats. For now, humans are visitors to the deep, not residents.

Verdict: Technically possible in theory, economically and biologically nightmarish in practice.

Score: 3/10 | Visionary, but wildly optimistic.

Category: “Close, But Not Quite”

Paris in the Twentieth Century - Jules Verne on the Eiffel Tower (Credit: Photo by Victor Ovies Arenas via Getty Images)

Videoconferencing & Remote Communication

From: In the Year 2889 / Paris in the Twentieth Century

Verne described systems resembling visual telephony, screens transmitting images and voices across vast distances. This sounded absurd in an era when the telephone itself barely existed.

Today, video calls are part of everyday life. However, Verne imagined these technologies as rigid, formal tools of bureaucracy rather than the casual, portable systems we use now. Worth also noting that many now believe ‘In the Year 2889’ was actually written by Verne’s son, Michel.

Verdict: Conceptually spot-on, culturally misjudged, perhaps not his idea?

Score: 6/10 | A strong hit with stylistic quirks.

Category: “Nailed It” | When Verne Saw the Future Clearly

Verne imagined a world powered by the sun (Credit: xiaokebetter via Getty Images)

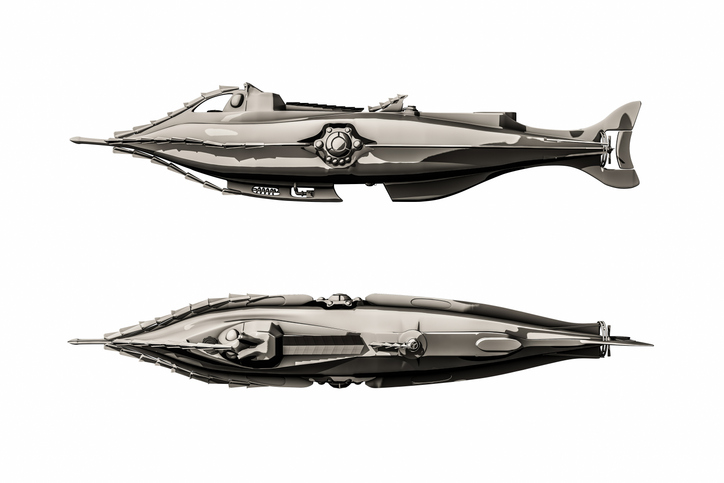

The Submarine

From: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

The Nautilus remains one of Verne’s greatest triumphs of prediction. Long before practical, long-range submarines existed, he envisioned a fully electric vessel capable of deep dives, extended underwater travel, and scientific exploration. Modern nuclear submarines may surpass the Nautilus in capability, but the core concept – self-sufficient underwater travel for military and research purposes – is astonishingly accurate.

Verdict: A masterpiece of speculative engineering.

Score: 10/10 | Dead-on brilliance.

Global Surveillance & Data Obsession

From: Paris in the Twentieth Century

Verne imagined a world obsessed with efficiency, statistics, and measurable productivity. Art and creativity are sidelined in favour of data, speed, and financial output. While he didn’t predict the internet or algorithms explicitly, the mindset he described feels eerily modern. Performance metrics, mass data collection, and an uneasy relationship between technology and culture define the 21st century.

Verdict: Not a gadget prediction, but a societal one and chillingly accurate.

Score: 9/10 | Philosophical foresight at its finest.

Solar & Electric Power

From: Multiple works

Verne repeatedly referenced alternative energy sources, including solar power and electricity, as the engines of the future. At a time when coal reigned supreme, this was a radical notion. While fossil fuels dominated for far longer than Verne expected, renewable energy is now central to global planning, innovation, and geopolitics.

Verdict: Early, idealistic, but ultimately correct.

Score: 9/10 | Ahead of the curve.

Bonus Round: Predictions He Didn’t Make, but Almost Did

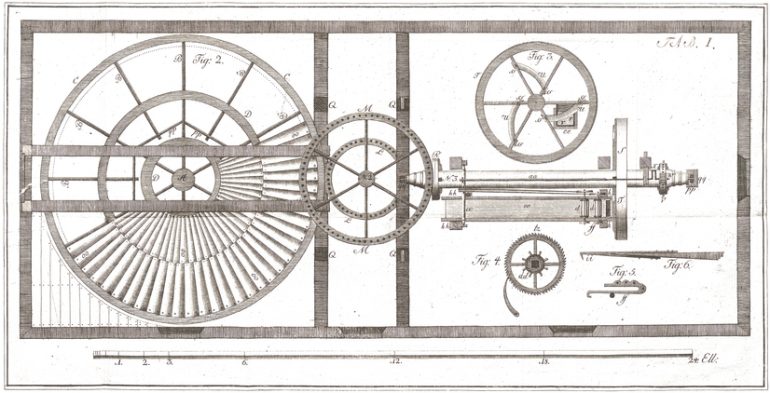

Verne's future worlds were mechanical, not digital (Credit: PATSTOCK via Getty Images)

Interestingly, Verne never fully anticipated computers, artificial intelligence, or digital networks as we understand them today. Yet many of his imagined machines rely on automation, rapid calculation, and information flow – suggesting he sensed the direction of travel, even if not the destination.

His future worlds are often hyper-mechanical rather than digital. Gears and engines dominate where code and software would later reign. This reflects the industrial context he lived in, but also highlights how deeply technology is shaped by its era.

Final Tally: How Did Jules Verne Do?

Jules Verne, 1828 - 1905 (Credit: Christine_Kohler via Getty Images)

Jules Verne wasn’t a prophet, and he didn’t always get the details right. Some of his ideas now seem charmingly naïve, others wildly impractical. But taken as a whole, his predictive record is extraordinary.

More importantly, Verne understood that technology would reshape how humans live, communicate, explore, and even think. He grasped that innovation would compress distances, challenge authority, and blur the boundaries between science and imagination. That insight, more than any submarine or space cannon, is why his work still resonates.

Overall Scorecard Verdict: Not perfect. Not precise. But undeniably visionary.