Every November, skies across Britain come alive with a crackle of fireworks, the scent of smoke, and cries of “Remember, remember the Fifth of November!” Bonfire Night commemorates the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605 – a conspiracy to blow up King James I and the Houses of Parliament. At its centre stood Guy Fawkes, a name that has echoed through history, folklore, and pop culture.

But how much of what we believe about Fawkes and his fiery legacy is actually true? Between centuries of retellings, nursery rhymes, and a masked antihero from V for Vendetta, the line between fact and fiction has blurred like smoke in the November air. The good news? We’re about to blow it all wide open.

A Brief Spark of Context

The gunpowder plotters (Credit: RockingStock via Getty Images)

Guy Fawkes was one of thirteen Catholic conspirators who plotted to assassinate the Protestant king and replace him with a Catholic monarch. Their weapon of choice: thirty-six barrels of gunpowder hidden beneath Parliament. But before dawn on 5 November 1605, authorities discovered Fawkes guarding the explosives. The plan blew up in their faces.

What followed was swift and brutal – arrests, interrogations, executions, and the birth of a national tradition. Yet over four centuries later, separating myth from history remains tricky business. Let’s sift through the ashes of legend and see which stories still hold fire.

Guy Fawkes’s Real Name Was Guido: FICTION

Guy Fawkes was born in York in 1570 (Credit: acceleratorhams via Getty Images)

He was born in York in 1570 and named Guy Fawkes. So, where does ‘Guido’ come into the story? While born a protestant, Fawkes converted to catholicism and fought in the Catholic Spanish army. It was during his time serving in that army that he adopted ‘Guido’, the Latin/Italian version of his given name.

Guy Fawkes Was the Mastermind of the Plot: FICTION

The announcement to decimalise was made in 1966 (Credit: CHUNYIP WONG via Getty Images)

While Fawkes became the face of the plot, he was not its architect. The scheme was conceived by Robert Catesby, who recruited Fawkes for his military and explosives expertise. Fawkes’s role was crucial, but he acted under direction, not from the top of the chain.

The Plot Aimed to Blow Up Parliament: FACT

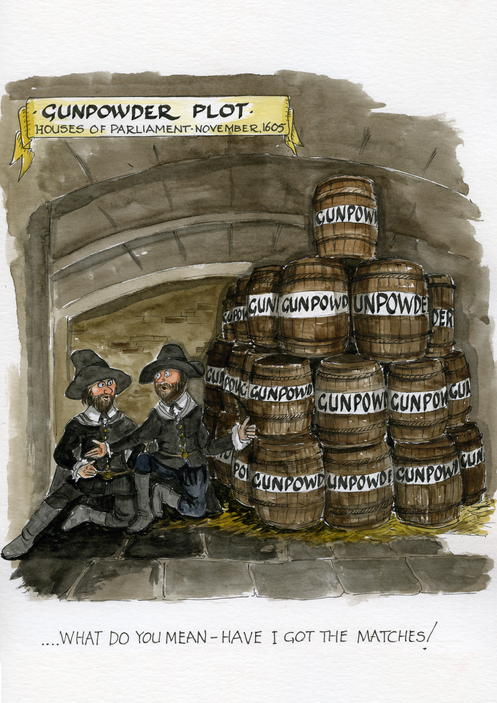

A cartoon of the gunpowder barrels in a cellar under the House of Lords (Credit: David Williams via Getty Images)

This one’s no exaggeration. The conspirators rented a cellar beneath the House of Lords and packed it with gunpowder barrels, disguised beneath firewood and coal. Had the plot succeeded, the explosion would likely have wrought devastation across Westminster.

The Plot Was Exposed by an Anonymous Letter: FACT

Lord Monteagle received an anonymous letter with a stark warning... (Credit: HUIZENG HU via Getty Images)

A few weeks before the planned explosion, an anonymous letter was delivered to Lord Monteagle, a Catholic peer, warning him not to attend Parliament on 5 November. Alarmed by its veiled threat – “they shall receive a terrible blow …” – Monteagle showed the note to the King’s ministers, who took it seriously. On the evening of 4 November, a search party led by Thomas Knyvet obtained permission to inspect the cellars beneath the House of Lords.

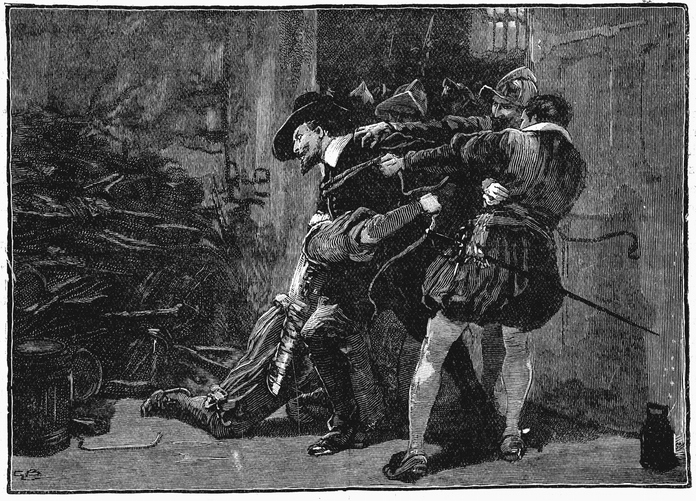

Guy Fawkes Was Caught Red-Handed: FACT

Fawkes was discovered and arrested in the cellar (Credit: Photos.com via Getty Images)

Fawkes was discovered in the early hours of 5 November, in a cellar beneath Parliament, in possession of fuses, lanterns, matches, and enough gunpowder to make a disastrous statement. His attempt to identify himself as “John Johnson” did little to mask his involvement.

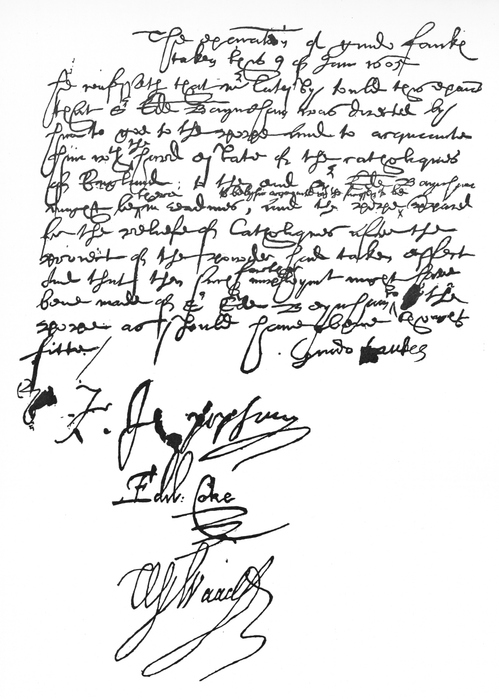

He Was Tortured on the Rack: FACT (probably)

Guy Fawkes' signed confession (Credit: powerofforever via Getty Images)

Fawkes was indeed tortured while held in the Tower of London, under the authority of King James I. The king’s warrant dated 6 November instructed that “gentler tortures are first to be used … and so by degrees proceeding to the worst.”

Early measures likely included suspension by manacles, his wrists shackled and perhaps hoisted off the floor to intensify pain. As for the rack, the picture is less certain. Some contemporary sources and later commentators suggest Fawkes was probably racked, especially given the deterioration in his handwriting and the confession signed in tremulous, shaky form. Yet historians concede there’s no definitive proof that the rack was used, only that the royal warrant permitted it.

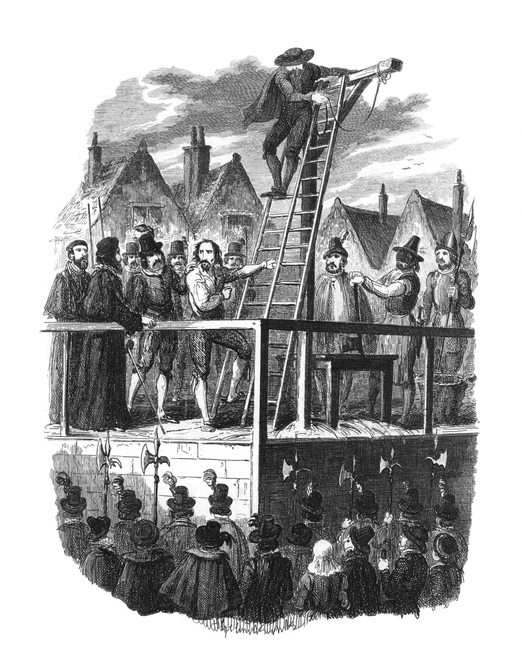

He Was Executed by Burning: FICTION

The execution of Guy Fawkes (Credit: golibo via Getty Images)

Despite the bonfires named after him, Fawkes was not burned alive. He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. On 31 January 1606, he went to the scaffold at Westminster. But by leaping (or falling badly) from the gallows, he broke his neck and died instantly – thus evading the full horror of his sentence’s later stages.

Bonfire Night Started Immediately After the Plot: PARTLY FACT

In the early 17th century, Parliament passed an Act of Observance (Credit: powerofforever via Getty Images)

In 1606, Parliament passed an Act of Observance, declaring 5 November a day of thanksgiving. Early commemorations included church services, prayers, and sermons. The more raucous public celebrations – bonfires, fireworks, effigies – gradually built over decades. The “Penny for the Guy” tradition emerged later.

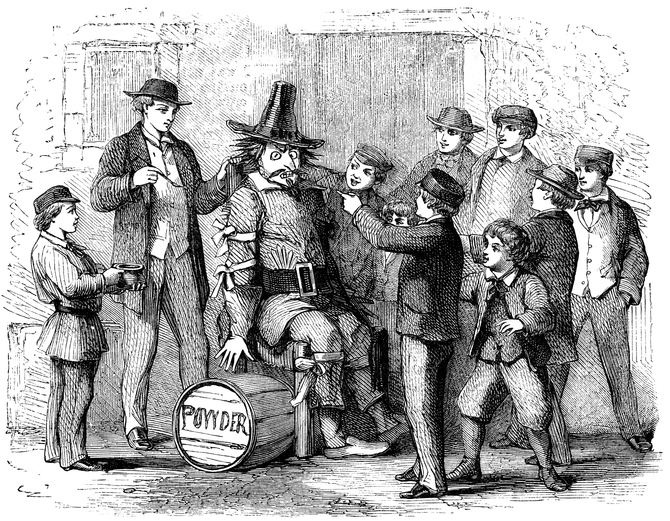

Guy Fawkes Night Was Always Family-Friendly: FICTION

An effigy of Guy Fawkes from the mid-19th century (Credit: TonyBaggett via Getty Images)

Early celebrations were frequently rowdy and politically pointed. Effigies of unpopular figures were burned; crowds sometimes clashed; and firework mishaps were not uncommon. It was later – especially in the Victorian era – that bonfire night became more regulated and domesticated, turning into the safer tradition many enjoy today.

The Nursery Rhyme Came from the Time: PARTLY FACT

Thomas de Ercildounson was mentioned in thirteenth century charters (Credit: Tetra Images via Getty Images)

The rhyme “Remember, remember the Fifth of November” evolved from post-Plot religious verse and propaganda. Early printings had different wordings. Over centuries it was refined into the version widely known today. Its roots lie in contemporary reaction, but its polished form is a later invention.

The Iconic Mask Came from the Film V for Vendetta: FICTION

The iconic Guy Fawkes mask (Credit: Tetra Images via Getty Images)

The stylised Guy Fawkes mask is not a cinematic invention. It originates from the graphic novel V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd. The 2005 film adaptation popularised it more broadly, but the iconic look began in print.

The Gunpowder Plot was secretly staged to discredit Catholics: FICTION

Spymaster Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (Credit: powerofforever via Getty Images)

Some theories propose that the 1605 plot was less a genuine insurrection than a cunning political trap. According to this narrative, the Crown, via the spymaster Robert Cecil, orchestrated or manipulated a group of Catholic dissidents into plotting regicide, all with the promise of immunity. In this version, unsuspecting Catholics – led by the idealistic Catesby faction – were drawn into the scheme, then publicly exposed, so that the government could unleash a wave of anti-Catholic propaganda, tighten restrictions, and cast all Catholics as eternal traitors. This is widely discredited by historians.

The Man, the Myth, the Mask

Ooh, aah...! (Credit: Katsumi Murouchi via Getty Images)

From Parliament’s cellars to the pages of dystopian fiction, Guy Fawkes’s story refuses to lie dormant. These days, though, it’s less about failed plots and more about hot chocolate, sparklers, and arguing over which firework was the most spectacular. The politics have cooled, the fuses are safer, and the only thing we’re lighting up now is the night sky.