Democracy – the system that puts power into the hands of the people – has a story as rich and complex as human society itself. From the small assemblies of the ancient world to the digital platforms of today, the idea that every voice should count is as important today as it has ever been.

But while today much of the world takes democracy and the right to vote for granted, for much of history, participation in the democratic process was limited to a privileged few and was seen as a marker of status and influence. Over the centuries, struggles for rights, revolutions, and reforms slowly broadened access, reshaping democracy into something far more inclusive and representative.

The journey from stones to scrolls, and ticking boxes on ballot papers to being able to vote online shows how the tools of democracy have changed. In this article, we’ll trace the fascinating evolution of voting.

What is the International Day of Democracy?

International Day of Democracy (Credit: Chinnapong via Getty Images)

The International Day of Democracy was established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2007 and first observed in 2008. It was created to promote and uphold the principles of democracy worldwide, encouraging governments and organisations to celebrate and raise awareness of democratic values.

This day is important because it provides an annual opportunity for the UN to review the state of democracy around the world, emphasise the need for inclusiveness, accountability, and equal participation, and highlight the essential connection democracy has with freedom, human rights, and peace.

International Day of Democracy 2025

Each year, the International Day of Democracy has a theme. In past years, themes have included Democracy & Political Tolerance, Strengthening Voices for Democracy, Engaging Youth on Democracy, and Navigating AI for Governance and Citizen Engagement.

According to the UN website – Democracy is a universally recognised ideal and is one of the core values and principles of the United Nations. Democracy provides an environment for the protection and effective realisation of human rights. The UN promotes good governance, monitors elections, supports civil society to strengthen democratic institutions and accountability.

But how did we get from sorting stones to counting clicks? Let’s find out.

Ancient Greece: The Birthplace of Democracy and Voting with Stones

Pnyx Hill in Athens, the site of one of the earliest ekklēsia (Credit: George Pachantouris via Getty Images)

Voting in Ancient Greece was where many of the ideas behind democracy first took shape, but it was also very different from today’s secret ballots. In Athens, around the late sixth century BC, male citizens gathered in open assemblies (ekklēsia) to vote publicly on things like laws and war decisions. Eligibility was limited – only freeborn Athenian men could vote. Women, slaves, and foreigners were excluded. Votes were usually cast by a show of hands. Another form of voting was the use of shards of pottery called ostracons to write names, from where the word ‘ostracism’ comes, as Athenians could also vote to banish or exile people from the city whom they deemed dangerous.

Another fascinating fact about the democratic process in ancient Greece was that many public offices were assigned by lottery to prevent corruption, and voting was an active, face-to-face communal event that combined civic duty with theatre, rather than the intensely secretive, personal act it is today.

Ancient Rome: Complex Voting and the Early Secret Ballot

Voting in Ancient Rome was done on wooden tablets coated in wax (Credit: clu via Getty Images)

Rome’s voting system was complex and inextricably linked with its class structure. Voting was tied to tribal groups, and citizens elected officials such as consuls. Roman citizens voted directly but voting was weighted by social class and property ownership, so the elite often controlled outcomes. Rome introduced a secret ballot system (leges tabellariae) around 139 BC, allowing people to cast votes anonymously on wooden tablets coated with wax. Voting was vital in selecting magistrates and shaping policy, but elections were also known for fierce competition, political violence, and vote-buying – ancient Roman politics was anything but dull!

Meanwhile, plebeians – common citizens such as farmers, labourers, shopkeepers and craftsmen who made up the vast majority of the population but lacked the power and status of the patricians, or elite classes – gradually gained more rights to vote, reflecting slow but steady inclusion. This centuries-long process (between 500 BC and 287 BC) was known as ‘The Struggle of the Orders.’

Medieval Europe: From Assemblies to Limited Voting

Renaissance Florence helped sow the seeds of modern voting (Credit: Suttipong Sutiratanachai via Getty Images)

After the fall of Rome, widespread democratic voting mostly disappeared in Europe, with governance dominated by monarchs and nobles. However, some local city-states and towns revived forms of voting within their merchant or guild communities, using meetings to decide matters like leadership or trade rules.

Eligibility was highly restricted, typically to wealthy landowners or merchants. Voting often took place with a show of hands or acclamations, not secret ballots, and was less about wide public participation and more about elite consensus. Despite this, these medieval seeds of voting helped preserve the idea of civic input, which blossomed centuries later during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, inspired by the classical past.

16th to 18th Centuries: The Slow Return of Voting

The English Civil War ignited demands for the people to have a say (Credit: RockingStock via Getty Images)

The centuries after medieval Europe saw voting take baby steps toward what we recognise today, but it was still a long way from modern democracy. During the Renaissance and Enlightenment, new ideas about rights, law, and government began to spread, especially among the European aristocracy and intellectuals. Voting remained limited mostly to elites – nobles, landowners, and wealthy men – who gathered in councils, parliaments, or town halls to make decisions. Voting methods varied from raised hands and voice votes to paper ballots, but secrecy was rare. Castles and town halls saw votes expressed by voices raised, written ballots, or simple shows of hands – secret ballots and universal voting were still far in the future.

These centuries laid the groundwork for the revolutionary changes to come, as power slowly shifted away from kings and toward representative bodies. Events like the English Civil War and American and French Revolutions in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ignited demands for the people to have a say, planting seeds for modern democratic elections.

Women’s Suffrage: Opening the Ballot Box

Suffragettes Emmeline & Christabel Pankhurst (Credit: Photos.com via Getty Images)

For centuries, voting was almost exclusively a man’s right. That started changing in the late nineteenth century with years of activism and protest. New Zealand was the pioneer, granting women full voting rights in 1893. Australia, Finland, the UK (in stages between 1918 and 1928), the US (1920), Germany, and Canada soon followed. The movement wasn’t just about voting but also – eventually – winning the right to run for office. While some countries embraced women’s suffrage early, others took decades longer, with some granting full rights only after World War II or later. This struggle transformed democracies worldwide and continues to inspire voter inclusion efforts today.

Suffrage in the UK

The fight for women’s right to vote in Britain was a marathon, not a sprint, and it was driven by determined women who refused to be ignored. The suffrage movement gained momentum in the mid-1800s with early campaigners like Millicent Fawcett, who led the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and believed in peaceful, legal methods including petitions and lobbying. However, frustration with slow progress paved the way for more militant tactics led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), founded in 1903. Their hunger strikes, protests, and civil disobedience made headlines and shook the establishment.

Other iconic figures included Christabel Pankhurst, a fiery orator and strategist, and Emily Davison, whose dramatic 1913 protest at the Derby became a symbol of sacrifice. The First World War shifted the debate further, recognising women’s contributions to the war effort. This led to the pivotal Representation of the People Act 1918, which gave voting rights to women over 30 who met property qualifications. Full equal voting rights with men finally came a decade later, in 1928, through the Equal Franchise Act, when all women over 21 were enfranchised, marking a historic victory for democracy in the UK.

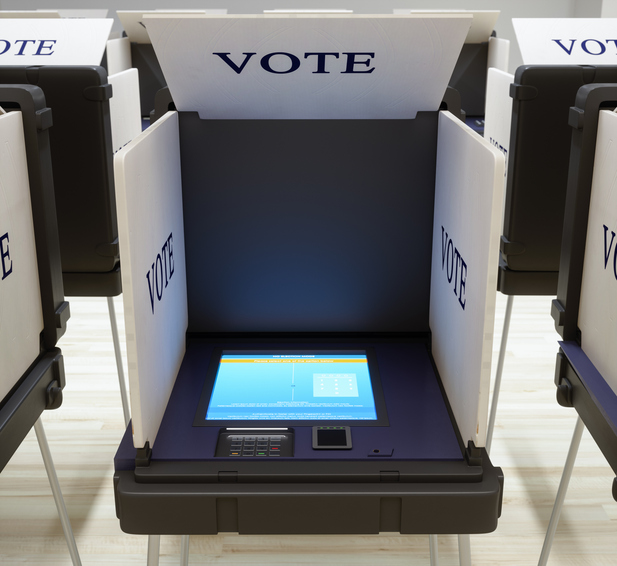

From Pebbles to Pixels - Modern Voting

From stones to screens... (Credit: onurdongel via Getty Images)

Fast forward to today, and voting has become a cornerstone of democratic societies worldwide – with universal suffrage the ideal where every adult citizen can vote regardless of gender, race, or wealth. Paper ballots replaced stones and pottery shards long ago, using printed slips marked in private booths. More recently, technology has introduced electronic voting machines and, increasingly, online voting options in some places, pushing the boundaries of access and convenience.

Modern voting aims to be secret, secure, and inclusive, though in practice challenges remain. What started as simple acts of stones and hands has evolved into complex systems designed to capture the will of populations all across the world.