History is littered with rulers who lived life on the outer limits of excess, their names forever linked with scandal, cruelty, and unrestrained indulgence. Roman emperors such as Caligula and Elagabalus stand among the most notorious. Yet even among such exalted company, the tale of Sardanapalus stands out – a ruler whose name became synonymous with decadence so extreme that it blurred the line between history and myth.

Could such a ruler have actually existed? History is torn as to whether he did at all. He’s often credited as being the last king of Assyria but even that basic fact is the subject of debate. Indeed, it’s worth noting that the legendary details of the life and death of Sardanapalus all come from Greek historian Diodorus, but aren’t matched or corroborated by Assyrian inscriptions or king lists from the time.

So what’s really going on? Was this a story based on real history lost to the mists of time, or fabled falsehoods created to blight the reputation of an ancient nation. Step into the world of Sardanapalus, where the only thing more excessive than the feasts was the fall.

Who Was Sardanapalus?

A 19th century illustration of Sardanapalus (Credit: ZU_09 via Getty Images)

According to ancient sources, particularly later compilations of a lost book called Persica by the Greek historian Ctesias – as relayed by Diodorus – Sardanapalus was a king who lived in the seventh century BC. He was said to have ruled over the vast Assyrian Empire from his capital at Nineveh, an ancient Mesopotamian city in the present-day area of Mosul in northern Iraq.

According to Diodurus, Sardanapalus – sometimes spelled Sardanapallus – was the son of Anakyndaraxes. Yet beyond such fleeting facts, the historical record is eerily silent, and nothing is known of his life with any certainty.

The stories that do survive depict him as a king who rejected the demands and responsibilities of royal rule in favour of a life devoted to pleasure and self-indulgence. He’s said to have spent his days secluded in his palace, surrounded by concubines, spinning clothes made of purple wool, and engaging in lavish feasts and sensual pursuits.

Diodurus went as far as saying that Sardanapalus exceeded all previous rulers in sloth and luxury. This reputation shocked his contemporaries and sowed deep discontent among both his subjects and the nobility, who saw his behaviour as unworthy of a king and a threat to the stability of the empire. But whether Sardanapalus ever truly existed remains a bone of contention.

Sardanapalus - Man or Myth?

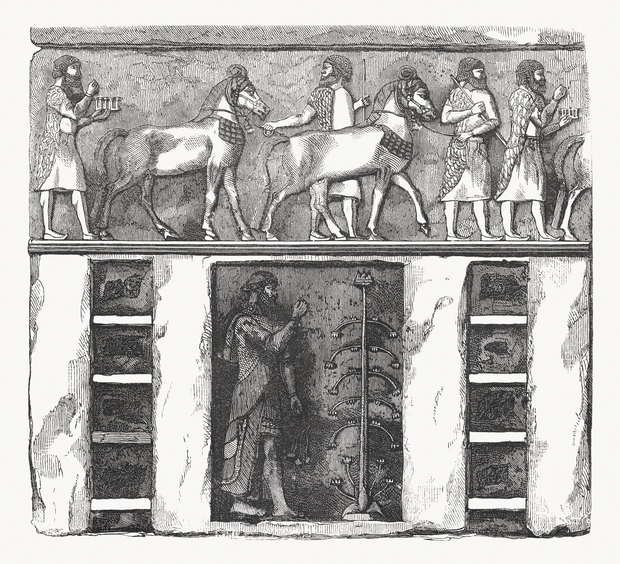

An engraving of Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (Credit: mikroman6 via Getty Images)

There’s no mention of a king by this name in the Assyrian King List, and many scholars believe Sardanapalus is a Greek corruption of the name Ashurbanipal, the last king of Assyria, or possibly a memory of his brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, who rebelled against Ashurbanipal and may have died when his palace was burned to the ground.

If this were true, there’s a huge disconnect between the legend and the known facts. Neither Ashurbanipal or Shamash-shum-ukin were known to have led hedonistic lifestyles. In fact the opposite is true. Both men were said to be brave, highly disciplined rulers who took their royal responsibilities seriously. Ashurbanipal in particular was said to have been a scholarly man who learned about history, mathematics, astronomy, zoology and botany. He was also a patron of culture.

Unhappy Campers - The Downfall of Sardanapalus

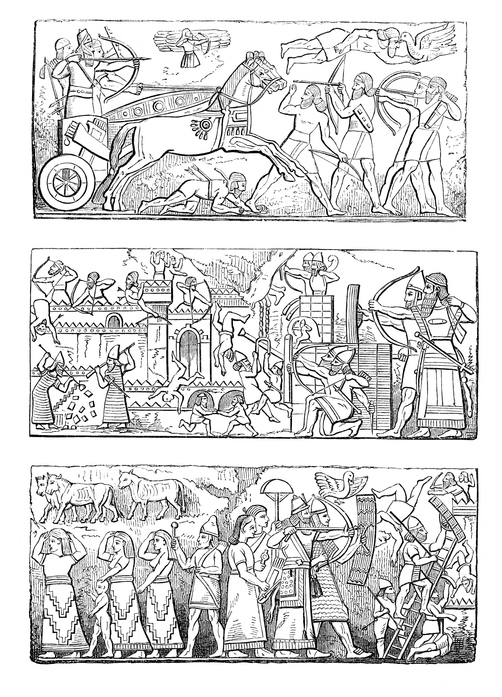

Assyrian bas-reliefs from the Palace of Sardanalapus at Nineveh (Credit: ZU_09 via Getty Images)

The downfall of the so-called last king of Assyria began with a conspiracy led by Arbaces, a powerful general from the Medes – an ancient Iranian people who inhabited the region known as Media, located in what is now western and northwestern Iran. Originally vassals of the Assyrian Empire, the Medes grew in strength and ambition, eventually playing a pivotal role in the downfall of Assyria itself.

The story tells that the Median general Arbaces, who served under Sardanapalus, became increasingly disillusioned with the king’s notorious excesses and his neglect of royal duties. Disturbed by Sardanapalus’s decadent lifestyle, Arbaces secretly forged alliances with other discontented groups, including the Babylonians, Persians, and Bactrians, and began plotting to overthrow the Assyrian king. It was said Arbaces amassed a formidable army which may have numbered up to 400,000 men.

When Sardanapalus got wind of the plot, he rallied his loyal forces and, in the initial clashes, managed to win several battles and drove his attackers back into the mountains. However, his confidence proved fatal. Believing the danger had passed, he relaxed his guard and celebrated with a typically lavish feast, only for Arbaces and his allies to launch a surprise assault which devastated the king’s forces.

The rebels pressed their advantage, killing Sardanapalus’s brother-in-law and commander-in-chief, and forcing the remnants of the royal army to retreat behind the walls of Nineveh. The city withstood a prolonged siege for two years, but in the third year, a catastrophic flood of the Tigris River breached Nineveh’s defences, resulting in the collapse of a section of the city wall and leaving it vulnerable and exposed.

Rather than face the ignominy of defeat and capture, the king put on one final, dramatic show.

The Death of Sardanapalus

The fiery death of Sardanapalus (Credit: clu via Getty Images)

As the flood waters opened up gaps in the city walls, Arbaces and his men stormed through the defences, determined to capture Sardanapallus. Yet according to the legend, the king had other ideas.

Realising defeat was inevitable, Sardanapalus gathered all his treasures along with his eunuchs and concubines into his palace, built a massive funeral pyre, boxed everyone and everything inside – including himself – and set it ablaze. Fittingly, the death of Sardanapalus was as extravagantly excessive as the life he had so recklessly lived.

Alexander and the Tomb of Sardanapalus

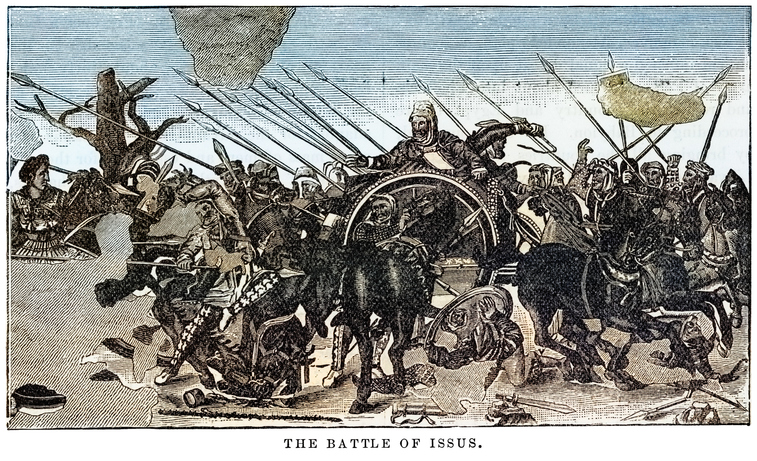

Alexander the Great at the Battle of Issus, 333 BC (Credit: mikroman6 via Getty Images)

For a king who may or may not have existed, the life of Sardanapalus was said to have been one of extreme decadence, excess, corruption, debauchery and hedonism, the likes of which may not have been matched before or since. The death of Sardanapalus was as dramatic as his life, and almost three centuries after his demise, one of history’s greatest military leaders is said to have visited his tomb.

On the eve of the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, Alexander the Great was reportedly shown what locals claimed to be the tomb of Sardanapalus, the legendary last king of Assyria. According to ancient sources, the tomb was located at Anchiale in Cilicia, near the Mediterranean coast in what is now southern Turkey.

The monument was described as a large stone structure bearing a relief of a king clapping his hands, and an inscription, allegedly in Assyrian cuneiform, which may or may not have been attributed to Sardanapallus himself. The inscription, translated by the locals, said “Sardanapalus, son of Anakyndaraxes, built Anchialus and Tarsus in a single day; stranger, eat, drink and make love, as other human things are not worth this.”

Some of the most renowned Greek and Roman writers – including Strabo, Plutarch, and Athenaeus, as well as the great Roman orator Cicero – recount various versions of the epitaph. Yet, as with much of the Sardanapalus legend, there’s no surviving evidence the tomb ever belonged to him, or that any Assyrian king died or was buried in Cilicia. If such a monument did exist, it was likely a much older structure that, over time, became entwined with myth, and mistakenly attributed to the infamous Assyrian ruler.

Sardanapalus in Art

Eugene Delacroix, painter of the most famous work depicting Sardanapalus (Credit: ZU_09 via Getty Images)

Despite – probably – being a mythical construct, Sardanapalus paintings, poems, and musical scores have been created by some of the most famous names in the history of the arts, all depicting him on one form or another as the epitome of excess, criminality, moral decay and ultimately, tragedy.

Aristotle | Nicomachean Ethics, Book I

Arguably the most influential philosopher and polymath who ever lived, Greek thinker Aristotle references Sardanapalus when discussing mistaken views of the good life. He notes that some people, including those of high status, equate happiness with a life of brute pleasure, likening them to Sardanapalus. Aristotle criticises this perspective, arguing that it is a slavish and animalistic conception of happiness, and uses the last king of Assyria as the archetype of a life devoted solely to sensual enjoyment.

Cassius Dio | Roman History, Epitome of Book LXXX

Writing in the third century AD, Roman historian Cassius Dio repeatedly compares emperor Elagabalus with Sardanapalus, using the Assyrian king as a symbol of supreme decadence and excess. Elagabalus is described as “the Assyrian” and is said to have lived in a manner so dissolute and rakish that he earned the nickname Sardanapalus.

Dante Alighieri | Paradiso

In the third part of his Divine Comedy written in the fourteenth century, Dante uses Sardanapalus as an example of ultimate decadence, stating, “Sardanapalus had not yet come to show to what use bedrooms can be put,” suggesting society had not yet reached such extremes of luxury and vice.

Lord Byron | Sardanapalus

Byron’s 1821 play presents the king as a pleasure-loving but ultimately tragic king, reluctant to embrace violence and war, whose reign collapses in rebellion and self-immolation. He’s depicted as both merciful and decadent, and as a ruler whose pursuit of peace and pleasure leads to his eventual downfall.

Eugène Delacroix | The Death of Sardanapalus

Perhaps the most famous Sardanapalus painting is the 1827 work by French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix. Displayed in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the oil on canvas depicts Sardanapalus reclining indifferently on a sumptuous bed, overseeing the chaotic slaughter of his concubines, servants, and horses as his palace is set on fire. The painting is a dramatic and violent vision of decadence and destruction, inspired by Byron’s play.

Edwin Atherstone | The Fall of Nineveh

Released in parts between 1828 and 1868, Atherstone’s epic thirty-book work the Fall of Nineveh, one of the longest epic poems in English and European literature at upwards of 200,000 words, portrays Sardanapalus as a criminal king who orders mass executions and ultimately burns his palace with all his concubines inside.

Hector Berlioz | Sardanapale

Berlioz composed a cantata in 1830 on the subject of the death of Sardanapalus, highlighting the king’s dramatic end in fire and chaos. Only a fragment of the score survives, but it reflects the Romantic fascination with his excess and demise.

Franz Lizst | Sardanapalo

Also based on Byron’s play, this unfinished opera from 1850 dramatises Sardanapalus’s final days and his relationship with his favorite concubine, Mirra. The music and libretto focus on the king’s doomed love and the revolt against his rule, emphasising his legendary decadence and tragic fate.

Sardanapalus: A Warning from History

Illustrations from 1870 depicting Sardanapalus at war (Credit: Grafissimo via Getty Images)

Whether Sardanapalus was a real king, a forgotten monarch, or a figure born entirely from myth, his story endured as a warning of the dangers of decadence and excess. The tales of his lavish lifestyle, the rebellion against his rule, and his spectacular, fiery death have little grounding in the actual records of Assyrian kingship.

No ruler named Sardanapalus or Sardanapallus appears in the Assyrian King List, and there’s no archaeological evidence to confirm that he ever existed. Most historians believe the legend is a blend of Greek storytelling and distorted memories of real Assyrian rulers, such as Ashurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, but the legend bears little resemblance to their true histories.

Yet, the legacy of Sardanapalus has proven remarkably enduring. His name has become a byword for ultimate indulgence and the dangers of unchecked luxury, inspiring generations of artists, writers, and composers. The fascination with Sardanapalus is less about historical facts and more about the symbolism – the seductive pull of pleasure, the perils of excess, and the inevitable collapse that follows corrupted rulers.