Every December, familiar melodies return like clockwork, filling living rooms, high streets and car radios alike. But their origins tell a far more surprising story. From protest songs and forgotten poems to humble beginnings that almost went unnoticed, the stories behind classic Christmas carols are anything but ordinary.

Some were reshaped by chance, others by controversy, and a few only found fame long after their creators were gone. So where did these festive staples really come from? Let’s take a closer listen.

Carols of Quiet Rebellion

Oliver Cromwell viewed festive celebrations as indulgent (Credit: mikroman6 via Getty Images)

Not all Christmas carols were welcomed with open arms. In fact, many were born in defiance of authority. In 17th-century England, Christmas itself became a controversial subject. During the rule of Oliver Cromwell and the Puritan government, festive celebrations were banned, viewed as indulgent and unbiblical.

Carols, closely associated with merriment and communal singing, were driven underground. Families often sang in secret, passing melodies down orally rather than committing them to paper. Songs survived not because they were officially endorsed, but because they were cherished at home. When Christmas traditions were restored after the monarchy returned in 1660, the music resurfaced too.

Silent Night’s Accidental Beginning

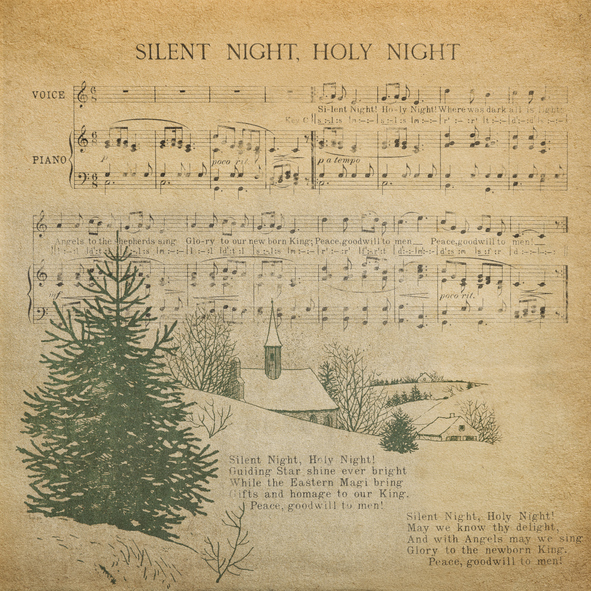

Silent night, holy night... (Credit: LiliGraphie via Getty Images)

Silent Night feels timeless, but its birth was surprisingly humble. It was written in 1818 in a small Austrian village, supposedly when the church organ broke on Christmas Eve. Faced with a musical crisis, priest Joseph Mohr brought a poem he had written earlier to Franz Xaver Gruber, the local schoolteacher. Gruber quickly set it to music for guitar accompaniment.

The result was gentle, simple, and perfect for the moment. Ironically, church authorities later worried the song sounded too much like folk music to be appropriate. They needn’t have worried. It travelled far beyond Austria, spreading through travelling singers and missionaries, and was eventually translated into hundreds of languages. In fact, it even played a role in the famous Christmas Truce of 1914, when soldiers on opposing sides reportedly sang it together across the trenches. Not bad for a song born of mechanical failure.

A Carol Built Over Centuries: Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

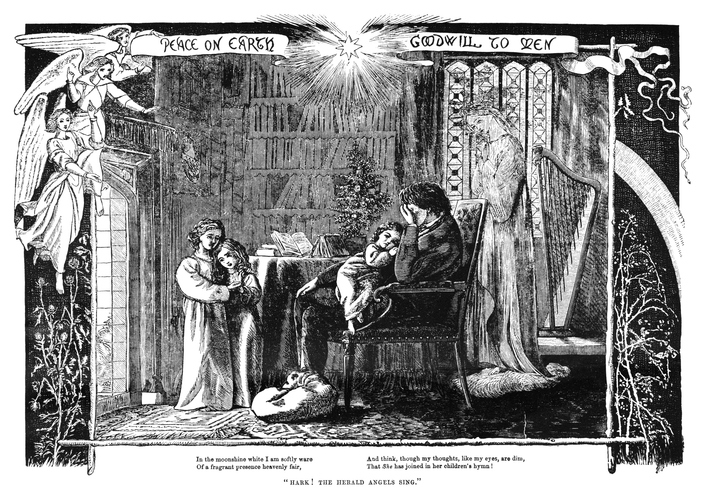

A Victorian newspaper illustration of Hark! The Herald Angels Sing (Credit: whitemay via Getty Images)

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing was a carol over a hundred years in the making. The story begins in 1739 with Charles Wesley, who wrote the original hymn as “Hark, how all the welkin rings.” It was theologically rich but lyrically dense, and its opening line baffled many congregations. Therefore, it soon underwent revisions, most notably by George Whitefield in 1753, who reshaped the first line into the version we recognise today.

And the tinkering didn’t stop there. Over the next two hundred years, editors continued to refine both the words and the melody. Dense phrases were trimmed, syllables smoothed out, and awkward lines reshaped whenever they threatened to trip up singers mid-verse. What’s more, the hymn drifted between tunes, never quite settling. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the lyrics were paired with Felix Mendelssohn’s music. Originally written for a celebration of Gutenberg’s printing press, both words and tune were adjusted to fit together. Mendelssohn himself didn’t think the tune belonged in church. History, once again, had other plans.

A Memory Game Melody: The Twelve Days of Christmas

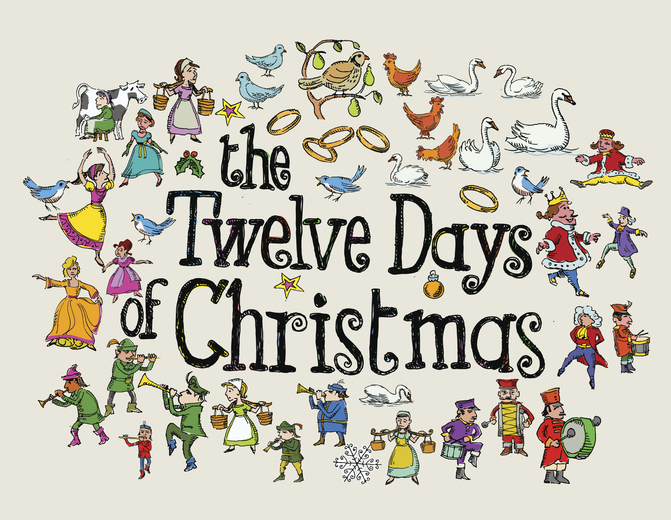

The Twelve Days of Christmas (Credit: smartboy10 via Getty Images)

This famously cumulative song dates back to at least the late 1700s. Contrary to popular belief, there’s no solid evidence it was written as a secret religious code during times of persecution. That particular tale seems to be a modern invention. Instead, the carol was likely a memory-and-forfeit game. Each singer had to remember the previous verses, and mistakes were punished with kisses, sweets, or small penalties. Suddenly, the length makes sense. As for the gifts, they probably reflected ideas of abundance and celebration rather than hidden meanings. Still, it’s fun to imagine the chaos of receiving 364 gifts by the final day.

A Song Born from Struggle: O Holy Night

O Holy Night (Credit: LazingBee via Getty Images)

Few carols possess the dramatic sweep of O Holy Night, and few have origins as politically charged. Written in France in 1847, the lyrics were penned by Placide Cappeau, a wine merchant and poet with socialist leanings. The music was the work of Adolphe Adam, a well-known opera composer best known for the ballet Giselle.

Initially embraced by the Catholic Church, the carol later drew criticism when Cappeau’s political views and rumours regarding Adam’s background became known. In America, however, O Holy Night found a new audience. Its line proclaiming that “chains shall he break, for the slave is our brother” resonated strongly with abolitionists in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Music Hiding A Message: O Come All Ye Faithful

Joyful and triumphant... (Credit: Jupiterimages via Getty Images)

This carol sounds straightforward enough, but its origins are surprisingly murky. Written in the 18th century, the original Latin version, Adeste Fideles, has been attributed to several authors, though John Francis Wade is the most likely candidate.

Some historians believe the lyrics contain hidden political symbolism, possibly supporting the Jacobite cause and the restoration of the Stuart monarchy. In this reading, the “faithful” are loyal supporters, and the call to Bethlehem is not entirely spiritual. Whether or not that theory holds water, the carol’s robust melody and confident invitation have ensured its popularity. Subtle rebellion or not, it’s hard to resist belting out the chorus.

A Victorian Christmas Reinvented

Victorian Christmas carol singers (Credit: Christine_Kohler via Getty Images)

If any era reshaped the Christmas carol, it was the Victorian age. The 19th century witnessed a revival of Christmas traditions, fuelled by industrialisation, urbanisation, and a growing nostalgia for perceived simpler times.

Carols played a central role in this reinvention. Collections such as Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern, published in 1833, gathered old folk songs and religious hymns, preserving melodies that might otherwise have been lost. This period also gave rise to entirely new compositions, including Once in Royal David’s City and O Little Town of Bethlehem.

Victorian carolling extended beyond churches. Groups sang door to door, raising money for charity or simply spreading festive cheer. The act of singing became a social glue, binding communities together during long winter nights. It was during this era that Christmas carols became inseparable from the idea of Christmas itself, not merely music, but ritual.

Music Across the Airwaves

Christmas music across the airwaves (Credit: onepony via Getty Images)

Christmas carols have also been pioneers in broadcasting history. In 1906, O Holy Night reportedly became the first song ever transmitted by radio. Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden played it on the violin during a Christmas Eve broadcast, astonishing radio operators who had expected only Morse code. Carols, with their widespread reach and simple melodies, were perfectly suited to this new medium. Radio ensured their survival in a rapidly modernising world, allowing them to travel farther and faster than ever before.

Ending On A High Note

Merry Christmas! (Credit: artisteer via Getty Images)

So why do these carols endure when countless others have faded? Partly, it’s familiarity. Hearing the same songs each year creates a sense of continuity, like unpacking old decorations or finding forgotten chocolates at the back of the cupboard. Moreover, carols balance simplicity with emotion. They’re easy to sing, their stories familiar. Perhaps that’s the real magic. And even if you groan when the first notes begin, chances are you’ll still break out into song.